Whose Knowledge is Valued?: Epistemic Injustice in CSCW Applications

0

Sign in to get full access

Overview

- Explores how "epistemic injustice" - unfairly discrediting people's knowledge and expertise - can arise in computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW) applications

- Highlights the importance of recognizing different types of knowledge and expertise in online communities

- Provides a conceptual framework for understanding how epistemic injustice can manifest and be addressed in CSCW systems

Plain English Explanation

The paper examines how certain people's knowledge and expertise can be unfairly dismissed or overlooked in online communities and collaborative technology applications. This phenomenon, known as "epistemic injustice," can prevent valuable perspectives and insights from being recognized and valued.

For example, in an online forum about a medical condition, the personal experiences and folk wisdom shared by patients may be seen as less credible than the formal knowledge of medical professionals. Or in a workplace collaboration tool, the practical know-how of frontline workers could be overshadowed by the theoretical expertise of managers.

The researchers propose a framework for understanding how these imbalances of epistemic power can arise, and how CSCW systems can be designed to be more inclusive of diverse forms of knowledge. This involves considering factors like who gets to set the rules for what counts as valid knowledge, how content moderation decisions are made, and whose voices are amplified or marginalized in the platform's algorithms and interfaces.

By highlighting these issues of epistemic injustice, the paper encourages CSCW practitioners to think more critically about whose knowledge is valued and whose is overlooked in the technologies they create. This can lead to more equitable and empowering online experiences for people of all backgrounds and expertise levels.

Technical Explanation

The paper draws on the philosophical concept of "epistemic injustice" to analyze how CSCW applications can systematically devalue or discount certain people's knowledge and expertise. [Intro link] The authors outline two key forms of epistemic injustice:

- Testimonial injustice: When someone's credibility is unjustly discounted, often due to prejudices about their social identity or group membership.

- Hermeneutical injustice: When someone is unable to make sense of their own social experiences because the conceptual resources to do so are lacking in the wider society.

The paper then explores how these dynamics can manifest in CSCW settings through factors like:

- [Content moderation link] Content moderation decisions that privilege certain types of knowledge over others

- [Algorithmic amplification link] Algorithmic curation and recommendation systems that inadvertently amplify some voices while marginalizing others

- [Participation barriers link] Platform features and norms that create barriers to participation for people with different forms of expertise

To address these issues, the authors propose design strategies for CSCW systems that cultivate "epistemic justice" by:

- Diversifying the forms of knowledge and expertise that are recognized and valued

- Empowering users to challenge and contest epistemic injustices

- Fostering collaborative sensemaking to develop shared conceptual frameworks

Overall, the paper highlights the important role that CSCW applications play in shaping whose knowledge and perspectives are seen as credible and authoritative. By adopting a more critical, equity-focused lens, the authors argue that these technologies can be redesigned to be more inclusive and empowering for people of all backgrounds.

Critical Analysis

The paper provides a valuable conceptual framework for understanding how issues of epistemic power and marginalization can manifest in CSCW applications. However, it acknowledges that the solutions proposed are still quite abstract and would require significant further research and development to translate into concrete design strategies.

[Limitations link] For example, the paper does not delve deeply into the technical challenges of implementing systems that can effectively detect and address different forms of epistemic injustice. Practical questions around scaling, automation, and user agency in content moderation processes are left largely unaddressed.

[Further research link] Additionally, the paper focuses primarily on textual interactions in online forums and communities. More research may be needed to understand how epistemic injustice plays out in other CSCW contexts involving multimedia content, real-time collaboration, and specialized knowledge domains.

[Questioning assumptions link] One could also question whether the paper's framing of "epistemic justice" as an inherent good is always appropriate. In some cases, the privileging of certain forms of expertise may be justified - for instance, deferring to medical professionals on matters of public health. The challenge is finding the right balance between inclusive participation and authoritative knowledge.

Overall, the paper offers a thoughtful and nuanced critique of how CSCW technologies can perpetuate unfair power dynamics around knowledge and expertise. While the solutions proposed are still high-level, the conceptual foundations laid here provide a valuable starting point for further research and development in this important area.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the critical issue of "epistemic injustice" in CSCW applications - the unfair dismissal or marginalization of certain people's knowledge and expertise. By drawing on the philosophical concept of epistemic injustice, the authors provide a framework for understanding how these power imbalances can arise through factors like content moderation, algorithmic curation, and participation barriers.

[Implications link] Addressing epistemic injustice in CSCW systems is crucial for ensuring that diverse perspectives and forms of knowledge are recognized and valued, leading to more equitable and empowering online experiences. The strategies proposed, such as diversifying recognized expertise and fostering collaborative sensemaking, offer a promising starting point for CSCW practitioners seeking to build more inclusive and empowering technologies.

[Future research link] While the solutions discussed remain conceptual, this paper lays important groundwork for further research and development in this area. Exploring the practical, scalable implementation of "epistemic justice" principles in CSCW applications will be an important next step in realizing the vision outlined here.

This summary was produced with help from an AI and may contain inaccuracies - check out the links to read the original source documents!

Related Papers

0

Whose Knowledge is Valued?: Epistemic Injustice in CSCW Applications

Leah Hope Ajmani, Jasmine C Foriest, Jordan Taylor, Kyle Pittman, Sarah Gilbert, Michael Ann Devito

Social computing scholars have long known that people do not interact with knowledge in straightforward ways, especially in digital environments. While policies around knowledge are essential for targeting misinformation, they are value-laden; in choosing how to present information, we undermine non-traditional -- often non-Western -- ways of knowing. Epistemic injustice is the systemic exclusion of certain people and methods from the knowledge canon. Epistemic injustice chips away at one's testimony and vocabulary until they are stripped of their due right to know and understand. In this paper, we articulate how epistemic injustice in sociotechnical applications leads to material harm. Inspired by a hybrid collaborative autoethnography of 14 CSCW practitioners, we present three cases of epistemic injustice in sociotechnical applications: online transgender healthcare, identity sensemaking on r/bisexual, and Indigenous ways of knowing on r/AskHistorians. We further explore signature tensions across our autoethnographic materials and relate them to previous CSCW research areas and personal non-technological experiences. We argue that epistemic injustice can serve as a unifying and intersectional lens for CSCW research by surfacing dimensions of epistemic community and power. Finally, we present a call to action of three changes the CSCW community should make to move toward its own goals of research justice. We call for CSCW researchers to center individual experiences, bolster communities, and remediate issues of epistemic power as a means towards epistemic justice. In sum, we recount, synthesize, and propose solutions for the various forms of epistemic injustice that CSCW sites of study -- including CSCW itself -- propagate.

Read more7/8/2024

🤖

0

Epistemic Injustice in Generative AI

Jackie Kay, Atoosa Kasirzadeh, Shakir Mohamed

This paper investigates how generative AI can potentially undermine the integrity of collective knowledge and the processes we rely on to acquire, assess, and trust information, posing a significant threat to our knowledge ecosystem and democratic discourse. Grounded in social and political philosophy, we introduce the concept of emph{generative algorithmic epistemic injustice}. We identify four key dimensions of this phenomenon: amplified and manipulative testimonial injustice, along with hermeneutical ignorance and access injustice. We illustrate each dimension with real-world examples that reveal how generative AI can produce or amplify misinformation, perpetuate representational harm, and create epistemic inequities, particularly in multilingual contexts. By highlighting these injustices, we aim to inform the development of epistemically just generative AI systems, proposing strategies for resistance, system design principles, and two approaches that leverage generative AI to foster a more equitable information ecosystem, thereby safeguarding democratic values and the integrity of knowledge production.

Read more8/22/2024

0

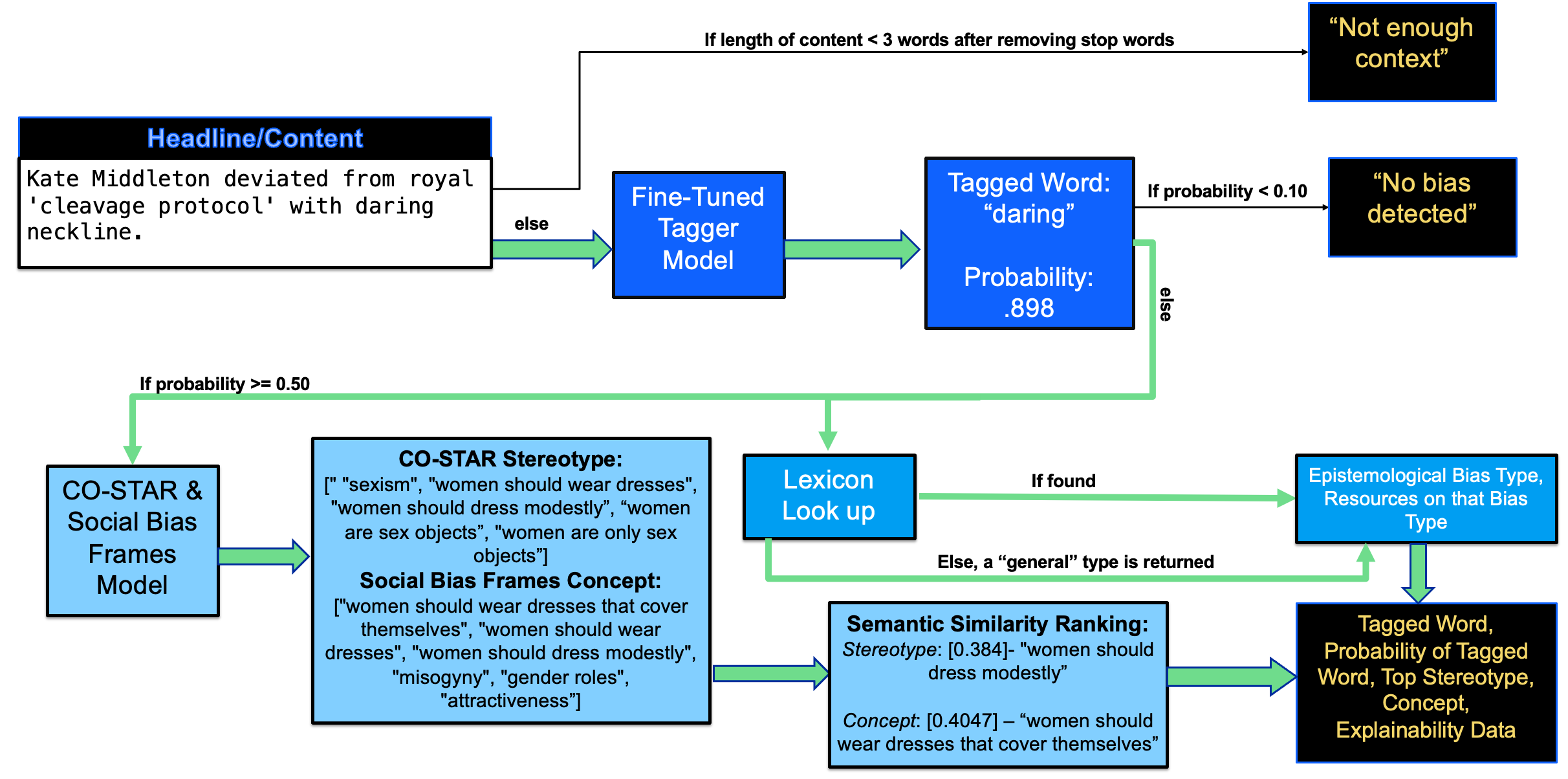

Epistemological Bias As a Means for the Automated Detection of Injustices in Text

Kenya Andrews, Lamogha Chiazor

Injustice occurs when someone experiences unfair treatment or their rights are violated and is often due to the presence of implicit biases and prejudice such as stereotypes. The automated identification of injustice in text has received little attention, due in part to the fact that underlying implicit biases or stereotypes are rarely explicitly stated and that instances often occur unconsciously due to the pervasive nature of prejudice in society. Here, we describe a novel framework that combines the use of a fine-tuned BERT-based bias detection model, two stereotype detection models, and a lexicon-based approach to show that epistemological biases (i.e., words, which presupposes, entails, asserts, hedges, or boosts text to erode or assert a person's capacity as a knower) can assist with the automatic detection of injustice in text. The news media has many instances of injustice (i.e. discriminatory narratives), thus it is our use case here. We conduct and discuss an empirical qualitative research study which shows how the framework can be applied to detect injustices, even at higher volumes of data.

Read more7/9/2024

🤖

0

Epistemic Power, Objectivity and Gender in AI Ethics Labor: Legitimizing Located Complaints

David Gray Widder

What counts as legitimate AI ethics labor, and consequently, what are the epistemic terms on which AI ethics claims are rendered legitimate? Based on 75 interviews with technologists including researchers, developers, open source contributors, and activists, this paper explores the various epistemic bases from which AI ethics is discussed and practiced. In the context of outside attacks on AI ethics as an impediment to progress, I show how some AI ethics practices have reached toward authority from automation and quantification, and achieved some legitimacy as a result, while those based on richly embodied and situated lived experience have not. This paper draws together the work of feminist Anthropology and Science and Technology Studies scholars Diana Forsythe and Lucy Suchman with the works of postcolonial feminist theorist Sara Ahmed and Black feminist theorist Kristie Dotson to examine the implications of dominant AI ethics practices. By entrenching the epistemic power of quantification, dominant AI ethics practices -- employing Model Cards and similar interventions -- risk legitimizing AI ethics as a project in equal and opposite measure to which they marginalize embodied lived experience as a legitimate part of the same project. In response, I propose humble technical practices: quantified or technical practices which specifically seek to make their epistemic limits clear in order to flatten hierarchies of epistemic power.

Read more4/19/2024